I joke a lot about how I am the only person left who doesn't hate Theseus but--fam, it is WILD to me, every time I slam up against that wall again. So this is your warning: I am UNAPOLOGETICALLY biased toward Theseus, and this post is just one gut-driven facet of my defense!

|

| Gustave Moreau, Athenians Being Delivered to the Minotaur, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Heracles had a choice, according to his myths, and chose glory. Achilles had a choice, according to his myths, and chose glory. Theseus had a choice, according to his myths, and chose glory. But today, culturally, Theseus (and to a lesser extent Achilles) gets the most heat for making that choice (and is reduced to a self-serving gloryhound only)--even though his choices generally better the circumstances for the people he ultimately wants to serve/lead (Athens).

Heracles's labors, in contrast, are most often framed inside his mythology as a means by which he ultimately serves himself--to redeem himself for the murder of his wife and children (or his children and nephews, or all three). He doesn't really have much of a choice about taking these labors on, because it's either DO THE THINGS, DIE, or BE FOREVER OUTCAST. And while those feats are impressive and worthy of awe, few of them are really improving things for anyone else--they're just increasing his fame. His initial choice to pursue glory despite his affliction of madness by Hera starts a war for Thebes (by another act of his madness), and then he is elevated for winning that same war he started, then he murders his family in another fit of madness and is forced to flee and seek atonement/purification through his labors. Is that really so much more sympathetic?

Theseus didn't HAVE to take the Isthmus road and clear it of the monsters who preyed upon travelers (the labors which are generally considered to be comparable to Heracles'). One could argue that he HAD to volunteer himself to go to Crete if he wanted legitimacy as a prince (and later king) of Athens, to prove himself to a people who did not know him, but it doesn't only serve him to do so--it serves as an attempt to liberate Athens from the oppression of Crete, which imho, served as a metaphor/explanation for the fall of what we today refer to as Minoan Civilization and the rise of what we consider Mycenaean/mainland Greek influence and dominance in that period.

BUT. It's curious to me, that we have culturally chosen to elevate the hero who is most famously acting for himself (Heracles) while dismissing and undermining the heroes who took action against powerful forces seeking to subjugate or harm others. The way we have maligned Achilles also, for example, the only hero who speaks out against a leadership that is wasting the lives of its army for the ego and selfishness of one man to fight a war that should never have been fought and reduced him to someone who selfishly sulks in his tent while others die for the Achaean cause--when it was on behalf of the Achaeans dying of plague he spoke out to begin with! It's not hard to see who that narrative might serve in the modern age.

Theseus is hated (it seems to me) primarily because he abandons or forgets Ariadne on the beach, and everything else he did (saving Athens from having to send its children to die in Crete in perpetuity, making the Isthmus road--the land connection between the Peloponnese and the rest of Greece--safe for travelers) has become meaningless in the wake of that one act, transforming the entire shape of his character in retellings of his myths--even though Ariadne ends up the consort of a god, elevated far beyond what she might have found as Theseus's wife and Queen of Athens. But how many women does Heracles take in the course of his adventures and pass off to other men or leave behind pregnant without looking back? Why don't we ever get upset on their behalf and condemn Heracles to the same degree? Why is it only Theseus who gets all that heat?

This is not to say that there are not valid critiques of these heroes, all of them. That we should not look at Heracles and Theseus and Achilles and their actions from a modern perspective and condemn what is obviously garbage behavior. None of them really hold up well as romantic literary heroes without some massaging of their stories (though I would argue that we hold up people just as flawed and problematic and selfish and even monstrous--or more monstrous even--as heroes today in and out of literature. We have only to look at the praise heaped upon authoritarian dictators, upon billionaires making bank by strip-mining the planet and exploiting labor, at famous figures who abuse their loved ones or those they employ, to see that we are not at all immune to that same impulse in the present.) But isn't it also just as legitimate to retell their stories in ways that allow us to reconnect with these heroes of the past? To make of these figures, these stories, someone worthy of the fame they'll likely never shake?

If they are only fiction, then maybe it makes no difference either way, except to give ourselves an aspirational ideal if we want it. But if they are and were bridges between the mortal and the divine, bringing them into the present in a way that makes them worthy (without dismissing utterly the context from which they sprang), that helps us find our own (modern) ways to the gods, feels not only important, but somehow necessary.

Leaving that aside for the moment, the most important thing I'm saying here is this:

If we are going to forgive Heracles for being a drunken brawling brute, for literal murder and the waging of city-destroying wars, for taking lover after lover with no shortage of dubiousness on the issue of consent to say nothing of the power dynamics in play, can't we not also, maybe, just CONSIDER not ALWAYS hating on Theseus, when most of his core mythology is just him trying (not always successfully or without consequence to others) to make things better?

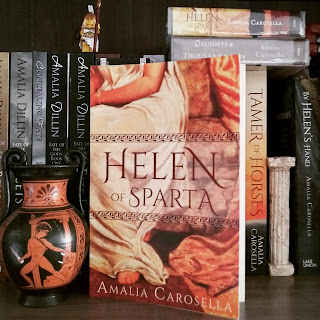

And if you want to read my take, you can start with HELEN OF SPARTA or TAMER OF HORSES!

Hi Amalia, I just want to let you know how grateful I am to have found an author who shares the same admiration towards Theseus as I do. At first, I thought I was the only person who saw Theseus as a person than a monster, but after I discovered one of your books Helen of Sparta. I was overjoyed to have discovered another person who admires Theseus the way I do.

ReplyDeleteThank you :)

It warms my heart to find a kindred Theseus spirit!!! I'm glad you found my books and my blog!!!

Delete