I am

absolutely fascinated beyond all reason by Aethra's relationship to Poseidon and how that relationship influences and alters the course of her life. (If you subscribe to

the Amaliad, this probably isn't news to you.)

“My Lord, how might Troezen serve you?”

“If I had come for Troezen’s service, I would have called to your father, the king,” Poseidon said, a ripple of laughter beneath his words. “This night, I have something else in mind. A bargain I would make with you alone, if you desire it.”

If I had been standing, I might have stepped back, but upon my knees, my face still held in his hand, I could only narrow my eyes and bite my tongue on a response that would give offense to a god. Because though he framed it as a choice, an offer I might decline, I was not certain he would be so generous if I denied him.

--The Lion of Troezen

CHOICE, right???

How much choice does anyone have when the offer comes from a god? I

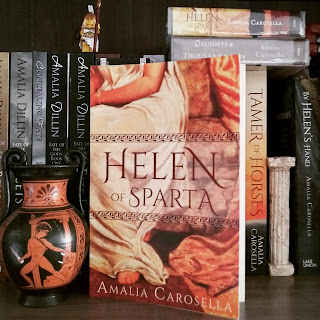

blogged about this topic previously and I think it's still (maybe even more) important and YES, this question of CONSENT is so much of why I am SO INTERESTED in Aethra's story, because of how I framed her relationship to Poseidon in HELEN OF SPARTA to begin with.

The heroes always get choices. ALWAYS. They always get a decision point. They can fade into obscurity or they can find GLORY AND FAME.

So where are the decision moments for everyone else?!

I've talked about the

choices and decision points heroes get, too, before--in regard to Theseus and how harshly he's judged in contrast to other heroes who make the same choice he does for arguably more selfish reasons, but I think it's important to engage with this from other perspectives, too.

Like: WHY IS IT that only the heroes are allowed explicit decision moments?

That's kind of rhetorical, we know that there was a limit in society/culture for anyone who wasn't a man in the periods these myths were recorded and preserved, of course, but does that mean WE SHOULD CONTINUE to impose that limit on characters and mythic figures of other genders? That we should continue to assume they were never granted them in our own retellings, now?

Let's step back from the most famous heroes we all know, whose stories are told over and over and over again--Heracles, Achilles, Theseus--and look at a different myth for a moment: the myth of Caeneus.

(CW: Rape.)

One of the Lapiths and favored by Poseidon, they were either propositioned or raped by Poseidon, and asked to be transformed into a man so that they would not have to bear his child or anyone else's--or according to Ovid, later, so they might never have to suffer a rape again.

A hero who became known thereafter as Caeneus.

Whether this exchange of favors was entirely voluntary really isn't clear. Did Caeneus have a choice about sleeping with Poseidon? Were they simply raped? The power dynamics at play would have made consent a tricky business no matter what, as we've previously discussed, so even best case scenario it's always going to be a little dubious on that score.*

For a little extra historical context though, the fact that Ovid of all writers seems to push the rape narrative so hard makes me inclined to think it might be a late Roman reading, or perhaps a bias against the idea of a woman being allowed to do anything with her life other than bear children without experiencing some kind of punishment—because Rome was, whew! Deeply invested in those traditional and strictly defined gender roles. PARTICULARLY during the reign of Augustus, who, if I recall correctly, pushed a family values agenda as he consolidated power and warped the Republic into an Imperium.

But setting aside that question, this myth still offers a tantalizing glimpse of something ELSE. Of Gods making BARGAINS with those they desire. Why should Poseidon have promised anything to Caeneus if there wasn't some kind of opportunity or right to refuse? And if that was the case, Caeneus may well have set the terms of the exchange, knowing Poseidon desired them.

So either Poseidon KNEW he had wronged them in an assault and offered the boon to make up for that, (which says something interesting in itself, about the inviolate right to bodily autonomy being recognized by the gods even if they didn’t always limit themselves by that recognition),

OR

More than just men had bodily autonomy and the power to choose the course their lives would take. TO TAKE CONTROL OF THEIR OWN FATE.

“I would have found you,” Poseidon promised, the slough of the sea coloring his voice. As if he’d read my thoughts, on my face or from my mind. “Readied and waiting, and you’d still have been mine. But I would have had you first, and bargained only after for what I’d taken, and the fates would have laughed in spite, for you would never have forgiven it, no matter what I offered.”

It was a splash of cold seawater dousing the flame of my desire, and I stepped back, my jaw tight with rage. “Should I have?” I demanded. “Should I now, when you say I deserve better, but in the next breath, admit you’d rape me?”

“You’d have enjoyed yourself, all the same, Princess,” Poseidon said, almost laughing at my response. As if it were all a game.

“Nothing would have been the same,” I snapped. “Bad enough that I trade myself for my father’s sake, for Troezen’s, but at least that is my choice to make. If you had taken it from me, I would have had nothing left. Nothing but a child I hated for the reminder it gave that my body would never be my own again.”

--The Lion of Troezen

The Myth of Caeneus is EXTREMELY important on any number of levels right now. On maybe every level right now.

Because CHOICE matters.

Because CHOICE has ALWAYS mattered.

The choice of HOW we live, and what we give of our bodies to others.

The choice of what body we want to live IN.

And when we're retelling these myths about women maybe we don't, ourselves, always have to choose to tell a story of rape. MAYBE there is more in the myths, even as they were preserved, than just the THEFT of that right to choose their own fate.

Or maybe this is just a very long-winded way of saying:

My retelling of Aethra's story in The Lion of Troezen? It's going to be something different.

*I've personally only bumped up against this myth because the Lapiths are Pirithous's people: Caeneus was at the Centauromachy, died in that battle with the centaurs, and interestingly, Polypoetes’s companion, Leonteus, appears to be his grandson. I'm sure there are people who know a lot more about it because it's an extant attestation of a trans man in ancient literature, which makes it particularly relevant to a lot of scholars right now.

Amazon | Barnes&Noble | IndieBound

_-_Neptune_and_Caenis_-_RCIN_401218_-_Royal_Collection.jpg)